Matching Client and Therapist Ethnicity Language and Gender a Review of Research

- Research

- Open up Admission

- Published:

Customer-therapist dyads and therapy outcome: Does sex activity matching matters? A cross-sectional report

BMC Psychology book 10, Article number:52 (2022) Cite this article

Abstract

Matching clients and therapist based on demographic variables might enhance therapeutic outcomes. Notwithstanding, research in this field is nonetheless inconclusive and non much is known about same-gender client therapist dyads in the context of cognitive behavioral (CBT) and psychodynamic methods. For this purpose, we studied the therapy outcomes of North = 1.212 participants that had received therapy (3 months–6 years) in Germany. The results showed a trend for same-gender client therapist dyads in terms of symptom reduction and quality of life specific to psychodynamic approaches. The latter applied specifically to female customer-therapist dyads. On the other hand, this trend was non fully axiomatic for CBT-based therapies. In decision, despite the robust sample and observed trends, it is not clear whether matching same gender dyads is advantageous with regards to symptom reduction and quality of life. Regardless, these results are preliminary and further studies are needed in order to notice out whether same gender client-therapist dyads enhance therapy outcomes or not.

Introduction

Identifying whether aforementioned gender client-therapist dyads heighten therapy outcomes or not, is highly relevant for clinical practice. In this way, the brunt of illness for patients and wellness care organization can be reduced. Past evidence related to customer therapist gender matching lacked statistical power or analyzed a single type of disorder. Hence, we examined several diagnosis in a robust sample, which distinguishes our research from past studies. Furthermore, previous evidence did non consider gender-matching in the context of specific psychotherapy methods. Therefore, our results were examined based on two established psychotherapy methods that are covered by the German health insurance, which is key when it comes to health-associated policies or individual preferences. In addition, nosotros illustrate a moving-picture show of the psychotherapeutic landscape in Federal republic of germany from the perspective of the patients, by providing detailed information on the issues and diagnosis of patients, including their symptom development.

Matching clients and therapist based on demographic variables is common clinical practise [1], as one possible arroyo in trying to optimize the fit between both parties (e.g., therapeutic relationship) also as psychotherapy outcomes [2, iii]. As suggested past past evidence, a strong therapeutic relationship predicts positive treatment outcomes [4], including positive effects in symptom reduction and full general ratings of success (amongst others); [iv,5,6]. Thus, information technology is plausible to assume that, in average, a skilful fit between client and therapist could be reflected in a strong bond / therapeutic relationship, as suggested by other researchers [7,viii,ix]. A proficient fit betwixt clients and therapist could also refer to equally having a similar understanding about managing emotions and attitudes [10,11,12]. Bowlby [13] reported that the psychotherapeutic relationship is comparable to the concept of attachment. Like in a parental or main caregiver human relationship, the psychotherapist offers emotional support, comfort and a "secure base of operations". In general, a positive therapeutic relationship is related to positive effects [4, half-dozen, 14, 15].

Ethnicity, historic period or personality variables take been too used every bit matching indicators. All the same, analyzing gender equally a matching indicator is widely recommended and is one of the most examined variables in counseling inquiry [iii, 16,17,18,19,xx]. Some researchers fifty-fifty discussed, that gender matched client-therapist dyads are essential for therapist to optimally adapt to the client'due south needs [16, 17]. Gender dyads or matching refers to client-therapist constellations of the same gender, e.m., female clients are assigned to female therapist, while male clients will be matched to male person therapist.

Theories suggest that individuals better identify and empathize with others if they believe to exist like to themselves [21, 22]. Accordingly, individuals develop certain gender-based behaviors or interactional styles and the convergence or divergence of these influences the quality of the human relationship and communication with others [23,24,25]. In this context, gender plays an important role, since information technology does not only refer to physical attributes, just to cultural aspects that touch on personality, attitudes, and behaviors [ii, 24]. The latter affects the individuals' world view in a way, that gendered schemas and social roles are internalized. As a result, social roles and gender expectations are reflected in specific behavioral interactional styles associated to gender [23, 25]. As an example, in western cultures men are typically socialized with traits attributed to authority and agency, such as striving for ability and independence. On the other hand, women are more than acquainted with communal traits or pro-social behaviors, such as solidarity and connectedness [26,27,28]. Correspondingly, both theories imply that aforementioned-gender client-therapist dyads have a greater convergence in terms of internalized gendered perspectives. For instance, men might instantly suppose that the male therapist will "get it" and consciously or unconsciously assume already an alliance [18]. Therefore, it is more likely that same-gender dyads share similar points of view and a comparable conceptualization of therapeutic related variables (due east.g., working brotherhood, well-being). These are thought to business relationship for a greater patient-therapist bail, translating into ameliorate therapeutic outcomes [iii, 28].

In the case of psychotherapy, positive outcomes refer to successful treatment, measured by a favorable treatment response, i.e., reduction of disorder specific symptoms, comeback in the quality of life, lower drop-out rates and even a better working alliance [29, thirty]. Many authors accept posited that addressing client preferences may boost therapy outcomes. In this regard, inquiry on client-therapist dyads has been reporting preferences towards same gender therapist [31,32,33,34,35]. However, in terms of outcomes empirical evidence shows inconsistent results. On the ane hand, studies revealed an comeback in psychiatric symptoms of gender-matched customer-therapist dyads [36, 37] reduced drop out [36, 38], better working brotherhood [3, xix], and greater satisfaction with the therapeutic human relationship [20, 33, 36]. Importantly, a previous study demonstrated that matched clients had significantly less utilization of intensive care services, saving costs effectually $one thousand (annually) per matched client [39]. On the other manus, authors have stated that gender matching is non a priority for clients neither an advisable predictor of the therapy processes and outcomes [1, 40,41,42], especially since the reported effect sizes are pocket-sized [3, 37, 43] and in some cases unknown [nineteen, 36]. A farther caption of these mixed findings may be related to limitations in methodological procedures, small sample sizes and heterogeneity concerning blazon of therapy.

Until now, symptom reduction has not been well documented in the context of same gender dyads and a specific types of therapy. For example, Staczan and colleagues [20] pointed out this gap and analyzed several treatment outcomes including symptom reduction in same gender pairings. Their written report showed highly significantly results in most of the studied variables in matched than in mismatched gender dyads. Nevertheless, no pregnant differences were shown amongst psychotherapy methods in terms of symptom reduction.

Regardless, the mentioned study did not examine cerebral-behavioral, behavioral, or psychoanalysis-based methods and if, some calculations included very modest sample sizes (eastward.thousand., Psychodynamic n = 4)—making findings susceptible to random fluctuations. Therefore, information technology is nevertheless not clear whether gender matching is relevant or not, depending on the type of therapy patients received.

The optimization of therapeutic outcomes may persistently reduce psychological symptoms and at the aforementioned time improve the quality of life of the patients [39, 44]. Identifying whether aforementioned gender client-therapist dyads enhance therapy outcomes or not has several advantages related to enhanced therapy outcomes (east.g., better quality of life, reduction of long-term financial burden for the health care system). Since cognitive-behavioral and psychoanalysis-based (i.due east., depth psychotherapeutic and psychodynamic therapy approaches) methods are covered by the High german public health insurance, price-effective measures that improve psychological interventions is a public/social concern.

Effective symptom reduction based on client therapist dyads is a very feasible procedure that can be easily implemented, if it turns out to exist a useful process that is evidenced based. Taking the described aspects into consideration the purpose of the nowadays study is to determine the relationship between aforementioned-gender client-therapist dyads and symptom reduction based on unlike types of therapies (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Psychodynamic approaches: e.g., Psychoanalysis and Depth psychotherapy). Based on previous findings, nosotros expect more positive outcomes in aforementioned gender customer-therapist dyads, compared to mismatched dyads. For this purpose, we assessed the post-obit outcome variables: Symptom reduction and quality of life in 2 different therapy approaches, 1. CBT and 2. Psychodynamic based methods.

Methods

Participants

The information of the study at hand were commissioned by the University of Leipzig and approved by their ethic committee (Approval number: WREBAM16102006DGPS). The data drove was carried out by the enquiry institute USUMA GmbH, Berlin. In general, north = 873 (72%) females and northward = 339 (28%) males with different mental wellness conditions participated in the study—a detailed clarification of the sample and psychiatric disorders is displayed in Tables i and 2. The length of therapy that participants received according to the therapy method is presented in Table 3.

Process

The information was collected in Federal republic of germany in the context of a cross-sectional study design. First, in a general and nationwide telephone surveys of the population, citizens in individual households who had received psychotherapy within the final 6 years or had been treated for at to the lowest degree 3 months were identified and asked if they were willing to provide information well-nigh their treatment. After informed consent, these participants were asked most their outpatient psychotherapy by trained interviewers in a standardized phone interview. All households were selected via the High german market place research institutes (ADM) by a telephone sampling "eASYSAMPLe" (Bik-Aschpurwis and Behrend GmbH 2009) that also identifies phone numbers that are non recorded in the phone book which (Gabler-Heder method) [45]. In this mode, a random selection of the households contacted could be ensured. Within the household, the target participant was also randomly determined using the "Sweden cardinal" [46].

The inclusion criteria consisted in screening target participants of at to the lowest degree 18 years one-time, who were treated within the past six years or had been treated for at least iii months. From these, North = iv.306 participants were targeted. A full of Northward = 1.913 (44.42%) people agreed to participate in the written report. Of those who were willing to participate, only Due north = one.212 (28.fourteen%) interviews were carried out (response rate 74%). Reasons for exclusion of those who agreed were: The current therapy time was likewise short (< 3 months), the therapy was too long agone (> 6 years), the target person refused the interview (north = 71; 5.85%), the connexion was interrupted or the person was non available (northward = 73; vi.02%). In n = 170 (fourteen.02%) cases, the interviewer found out that the target person had received physiotherapy rather than psychotherapy.

Measures

The current study was based on questions that reflect the outpatient psychotherapeutic care in Deutschland from the patient's point of view, as previously reported [47]. The standardized telephone interview independent questions from "Consumer Reports" which were based on the method of Seligman's "Consumer Reports Study" [48]; German version, [49] and which was supplemented by further questions apropos the evaluation of psychotherapy. Such consisted in information almost several aspects including patients' diagnosis (e.g., anxiety disorders, depression, eating disorders), illness duration and assessment of the treatment too every bit type of psychotherapy method (east.k., CBT, psychoanalysis, depth psychotherapy). For this purpose, the participants were asked: "What symptoms/complaints prompted you to seek therapeutic help?" The responses of the participants were rated past trained interviewers based on four predefined ICD diagnosis (i.e., anxiety disorders, low, addictive behavior, eating disorders) and other somatic symptoms or complaints (east.g., coping with somatic affliction, sexual problems, work related conflicts). These diagnosis and symptoms were called, considering they are the most prevalent in Germany and most of the patients seeking psychotherapy are affected past these conditions as stated past the federal offices of statistics [l] and the lodge of psychiatry and psychotherapy [51].

The general state of listen of the participants was assessed at the showtime of therapy, which was reported on a 5-point scale from "i: very bad" to "5: very skilful". To gauge the degree of symptom reduction in the corresponding ICD diagnoses of those who completed treatment, the participants were asked: "Did the therapy helped to alleviate the symptoms / problems you sought aid for?" The answers were categorized as followed: ane = "I am doing a lot better", 2 = "I am doing slightly better", 3 = "… no modify", iv = "… I am doing worse", 5 = "…not certain/don't know". For the cess of the duration of the handling, the participants were asked to study how many sessions they had completed from the beginning until the cease of treatment. A therapy session last 50 min in Germany.

For the purpose of the present study, nosotros assessed the quality-of-life domain. Patients rated their perception in a self-written report calibration from 1 to 5 (i = "I am doing a lot ameliorate", 2 = "I am doing slightly improve", 3 = "… no alter", iv = "… worse", v = "not sure/don't know").

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 24.0) and R [52]. For the present written report, we calculated a 2 (therapists' sex activity) × 2 (patients' sexual practice) between ANOVA with an blastoff-level of = 0.025 (Bonferroni adjustment), which takes into business relationship multiple testing. Subsequently, mail service-hoc-tests (i.eastward., estimated marginal means and bonferroni adjusted pairwise comparisons) were computed to specify differences throughout the comparisons of dyads of the dependent variables. As an effect size we reported partial η 2 with a 90% confidence interval. We tested the assumptions for the ANOVA (e.g., normality of residual distribution, homogeneity of variances) showing a normal distribution (F\(\le \hspace{0.17em}\)one.62, p ≥ 0.183). Regardless, the Shapiro Wilk was p < 0.001 besides as skewness and kurtosis demonstrated a low-cal divergence (i.e., for kurtosis the largest deviation was iii.44 and for skewness 0.75). Nevertheless, the ANOVA remains robust fifty-fifty if the normal distribution is non given, as demonstrated past Schmider and colleagues [53].

Results

Therapy setting

The majority of the psychotherapist were female person (57%), with a degree in Psychology (71%). Xl seven per centum of the respondents mentioned behavioral therapy, 41% therapy based on depth psychology and 5% psychoanalytic therapy equally a handling method, which was implemented as individual psychotherapy in 91% of the cases. Four per centum of the participants reported receiving a different psychotherapy method other than the higher up mentioned and three,6% were not sure nigh the method received. These latter mentioned groups were not included in the analyses, since the psychotherapy method was not clear. The 698 subjects who had completed therapy had an average of 48 sessions (SD ± 68.half-dozen) and a median of 30. There were no significant differences in terms of the boilerplate treatment length across therapy methods (F(3, 479) = 2.43; p = 0.064) – see Table 3. Forty three pct of all respondents had received outpatient psychotherapy in the by. Fifty five percent of all participants took medication for their mental health status.

Outcomes

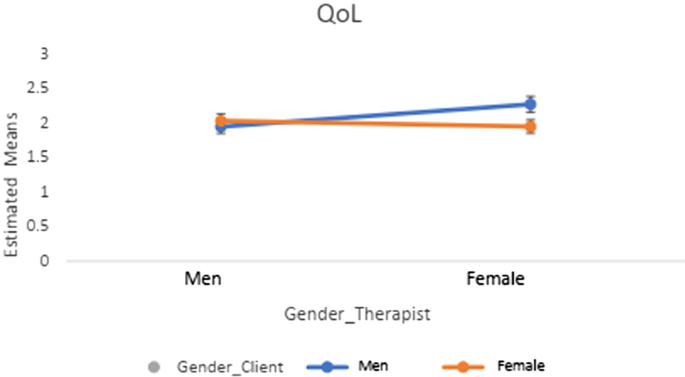

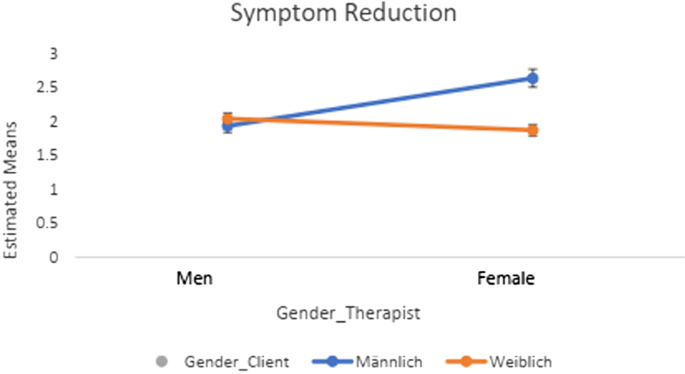

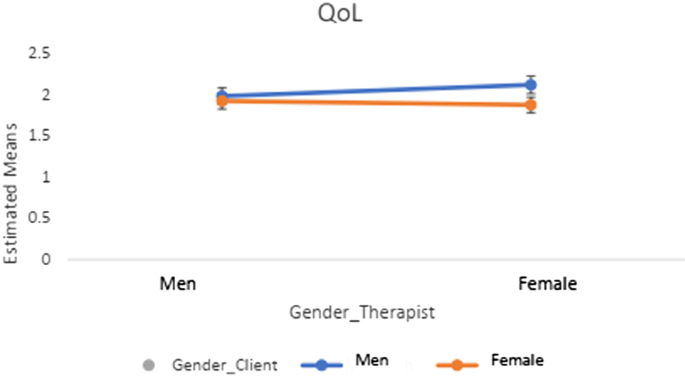

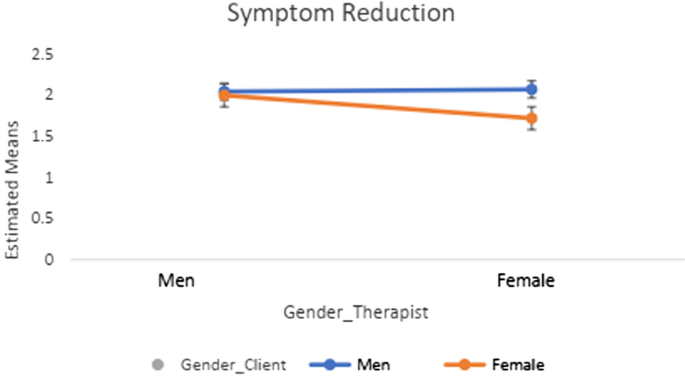

Tables 4 and 5 show the results of the 2 × ii ANOVA and post-hoc tests (Figs. one, 2, 3, four) regarding client-therapist dyads by therapy arroyo and examined variables (i.east., symptom reduction and QoL). Neither the gender of the client nor of the therapist indicated a significant effect for symptom reduction / QoL in the two therapy-approaches (F\(\le \hspace{0.17em}\)3.28, p ≥ 0.070, η 2\(\le \hspace{0.17em}\)0.042).

Post-hoc tests in QoL in psychodynamic-methods

Postal service-hoc tests in symptom reduction in psychodynamic-methods

Postal service-hoc tests in QoL in CBT-methods

Post-hoc tests in symptom reduction in CBT-methods

Further, none of the interaction furnishings demonstrated a significant result (run into Tables iv, five; Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4). The results of the post-hocs test revealed the post-obit outcomes. For CBT-methods female therapist matched with female person clients reached a significantly amend outcome in QoL compared to male therapist matched with male or female person clients. Concerning psychodynamic approaches, female person therapist matched with female clients reached a significantly better outcome in QoL compared to male person therapist matched with male or female clients. Male clients matched with male therapist showed a significant comeback compared to female clients matched with male person therapists. With regards to symptom reduction, female person therapist matched with female clients obtained significantly superior results than female therapist matched with male person clients (run across Tables iv, 5). Overall, the postal service-hoc tests indicated a positive outcome towards a same gender client-therapist matching especially for the female gender (vs. male client-therapist dyads) in QoL and symptom reduction within psychodynamic approaches vs. CBT-methods. For the latter, merely the dyad female person client and female person therapist in QoL was significant (see Tables 4, 5).

Diagnosis of the patients and symptom reduction descriptives are illustrated in Table 2. To make up one's mind the former, the participants were asked to report their complaints and symptoms that were crucial for seeking outpatient psychotherapeutic help. The majority of the respondents reported depressive (85%) and anxiety related symptoms (63.3%), while a minority sought outpatient psychotherapy due to addictive behaviors (thirteen.5%). Eighty iv percentage of the participants rated their initial condition at the beginning of therapy as "very bad" or "bad" (M = 1.72, SD ± 0.80).

Table 2 also depicts the accented and relative frequencies of the diagnosis and complaints reported as reasons for seeking handling besides as the distribution of the answers to the five categories to the question: "Did the therapy helped to alleviate the symptoms / problems you sought help for?" As demonstrated, virtually of the patients answered this question by "feeling much ameliorate" at the time they were asked to rate their perception of symptom alleviation after psychotherapy treatment. Improvement rates over 50% were observed in the post-obit variables: Suicidality (58.eight%), anorexia nervosa (56.2%) and bulimia nervosa (51.1%), panic attacks (50.6%). On the other mitt, the "deterioration rates" were consistently below five%, with the exception of "Issues in the workplace" = six.2%.

Of those participants who completed treatment (n = 698, mean therapy duration 15.75 months ± SD 15.77, 48 sessions, SD ± 68.six), they experienced an improvement in their complaints and problems after an boilerplate of approx. 50–56 treatment hours. Respondents who assessed their condition as "unchanged" completed an average of 35 therapy hours.

Discussion

The purpose of the study at hand was to decide the human relationship between same-gender client-therapist dyads and therapy outcomes (due east.yard., symptom reduction and QoL) based on different types of therapies (i.e., CBT-Methods and psychodynamic approaches). Birthday, the main findings did not support the epitome of improved treatment outcomes in same gender customer-therapy dyads. Nonetheless, based on our analyses one could speak of a trend in favor of same gender client-therapist (female-female) in terms of symptom reduction and quality of life in the context of psychodynamic approaches, compared to CBT-based psychotherapy. This latter consequence is in line with previous research showing no effect of same gender customer-therapist dyads [1, 40, 54, 55], fifty-fifty if not specific to CBT-based approaches. In add-on, the former finding was not consistent with the literature showing a positive upshot of same gender client therapist dyads on treatment outcome describing a better identification with similar others. Such understanding implies that same-gender customer-therapist dyads are more than likely to have a greater convergence in terms of internalized worldviews [18, 24, 25], consequently reflecting in enhanced therapy outcomes [3, 26, 28]. A possible explanation for the deviation between this and our results could be peradventure due to a lack of statistical ability. Our study only revealed a trend in favor of female customer matched with a female therapist rather than a significant issue. Thus, this corresponds with the results revealed in the nowadays report only at a descriptive level.

Notwithstanding, if considering the trends in the current study the better identification with similar others mostly applied to psychodynamic approaches. For the CBT-based psychotherapy QoL was enhanced in the female client-therapist dyad, while no other significant outcome was revealed in symptom reduction. Concerning psychodynamic approaches, merely a trend towards an interaction issue (gender-matching) was observed.

Of greater relevance, are the significant mail-hoc examination revealing a female effect: i.due east., generally female therapist matched to either female or male reached significantly better outcomes in QoL in both therapy approaches, compared to male therapist matched to males or females. Further, symptom reduction was also significantly greater in female person customer-therapist dyads (vs. male person-male dyads) if treatment was based on psychodynamic approaches. In other words, it is suggested that there is a tendency of female person and male clients to benefit more from treatment provided by female therapist (vs. male therapist), as reported in the past [3, 37, 43, 56, 57]. A possible explanation could exist that female person therapists are more responsive and empathic towards their clients. In improver, clients of both genders also tend to reply in a more positive mode to a female therapist at the kickoff of the treatment, which might influence the remaining treatment grade, as supported past previous bear witness [56,57,58].

The results in psychodynamic compared to CBT can be explained by the type of therapy methodology. Psychodynamic therapies (e.one thousand., depth psychotherapy/psychoanalysis) put more emphasis in interpersonal aspects (e.g., attitudes towards females or males), hence suggesting a greater relevance of gender [27, 28, 59], while CBT-based approaches tend to focus on modifying disorder specific behaviors. In depth psychotherapy, transference and countertransference are central aspects, whereby both, the gender of the client and the therapist may influence the therapeutic relationship [60]. For example, Tolle and Stratkötter [61] revealed that in same-gender therapy dyads transferences of both genders were reported, while in gender-mismatched dyads, the gender of the transference figure corresponded with the biological gender of the person. Nonetheless, the psychodynamic assumption of different transference patterns along gender boundaries is controversially discussed in depth psychology literature [62]. A basic supposition is that the gender of the therapist triggers (by) images in clients, which affect the interpretation of their "reality" by which transferences are build. The therapists react to this with countertransference or empathic responses, which are likewise influenced by gender part stereotypes [59].

An additional explanation of this female effect could be that in therapies using transference interpretations (equally in the case of depth psychotherapy and psychoanalysis), women experience the human relationship towards their therapist as an "affectively expressive" brotherhood. With male patients, female therapist might adjust the working relationship to the needs of their male clients and may grant or foster greater autonomy [63]. Additionally, it is conceivable that CBT-approaches and male person-male customer-therapist dyads may also fulfil the need for more than altitude and autonomy in male clients [63].

In spite of these findings, the therapeutic process is complex and might not be dependent on gender just. Importantly, our results are based on an observational rather than on an experimental sample and only pointed out a tendency with small to medium effect sizes. In improver, the outcomes of the present study must be interpreted with circumspection, since the results are based on the subjective perception of patients without considering the point of view of the therapist. Another limitation refers to the blazon of information collection. The results of the present study are based on a retrospective view and on a standardized interview rather than on validated instruments, making findings less comparable and perhaps less reliable. With regards to the latter business organization, fifty-fifty if retrospective studies are a valid method to collect information, such harbor advantages and disadvantages, as every other method. For example, it is known that cognitive processes (eastward.grand., memory) are not isolated from the electric current country of mind. Specifically, emotions and motivations might influence our perception and the judgments we make near the present and the by. Thus, in some cases, retrospective reports may not accurately represent specific recollections of information and rely on estimates and inferences [64, 65]. This reconstruction process could be a source of memory mistake, that might lead to a biased event, e.g., under or over-reporting of symptoms. Over-reporting tends to be greater for long term period events, when compared to brusque term periods [66]. Thus, it is possible that our participants might have overrated their symptoms, the longer ago the therapy was. Further, longer retrieve intervals could be associated with lower reliability of call back, and thus with a higher measurement error [65]. Fifty-fifty so, the recall intervals are distributed randomly across the different group variables. Hence, it is not expected to have adverse effects on the tests or the analyses. If anything, less reliable measurement / higher measurement error would rather pb to less statistical power and thus we would erroneously reject our hypothesis. Still, taking these aspects into consideration, further studies are needed to see how these results replicate.

Moreover, nosotros observed a gender disproportion, specially since more female than males participated in the study. In this respect, there is also a gender imbalance with regards to the therapists, since more females compared to males participated. Thus, information technology could be more probable to have a college female person matching in client-therapist dyads. This situation however reflects the current occupational distribution of psychotherapist in Germany. Information technology is estimated that around lxx% of the therapist are female, with a rising tendency [67]. A farther limiting aspect concerns the smaller sample sizes in the variable symptom reduction (vs. to QoL) for both therapy methods; which compromises its representativeness. Farther studies would benefit from larger samples in this domain. Perhaps time to come studies could target a greater responder rate by collecting data face-to-face. Possibly, an disability to create and maintain rapport vial telephone could accept affected the compliance to participate, considering not seeing the facial expression or body language of the interviewer might have negatively affected the response rate. Finally, our results excluded participants, who were in therapy for less than iii months. Hence, sudden gains or worsening of symptoms in this menstruation of fourth dimension is unknown.

In sum, a remarkable strength of the nowadays study is the large sample and the diverseness of disorders that patients reported, compared to past studies. Moreover, nosotros examined nearly widespread psychotherapy methods covered by the health insurance in Germany, which is relevant for public health related policies, economy and for individual choices, when seeking therapy. In addition, related studies could do good from including the perspective of the therapist in the analyses.

In conclusion, a recommendation to match same gender dyads in the context of psychotherapy is non quite clear based on our results. Therefore, more studies looking at the human relationship betwixt treatment consequence (due east.one thousand., symptom reduction in initial diagnosis) and the quality of the working alliance in the context of client-therapist gender matching with validated scales (e.grand., Symptom Bank check-List-90, Patient Wellness Questionnaire, Eating Disorders Inventory, Working-Alliance, Client Zipper to Therapist Scale) are needed to shed light on the revealed trend of the present study. This could allow a clarification whether or not same gender matching is relevant, especially in the context of depth psychotherapy approaches in terms symptom reduction and quality of life. If so, the results could be useful for health care policies and for clients in terms of decision-making when seeking psychotherapy.

Availability of information and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding writer on reasonable request.

References

-

KS Bhati 2014 Outcome of client-therapist gender match on the therapeutic human relationship: an exploratory assay Psychol Rep 115 2 565 583

-

H Brattland JM Koksvik O Burkeland CA Klöckner ML Lara-Cabrera SD Miller B Wampold T Ryum VC Iversen 2019 Does the working alliance mediate the effect of routine outcome monitoring (ROM) and brotherhood feedback on psychotherapy outcomes? A secondary analysis from a randomized clinical trial J Couns Psychol 66 234 246

-

MB Wintersteen JL Mensinger GS Diamond 2005 Exercise gender and racial differences between patient and therapist affect therapeutic alliance and treatment retention in adolescents? Prof Psychol Res Pract 36 4 400

-

Horvath AO, Del Re AC, Flückiger C, Symonds D. Alliance in individual psychotherapy. 2011.

-

LG Castonguay MJ Constantino MG Holtforth 2006 The working alliance: where are we and where should we go? Psychother Theory Res Pract Railroad train 43 three 271

-

S Zilcha-Mano N Solomonov H Chui KS McCarthy MS Barrett JP Barber 2015 Therapist-reported alliance: is it really a predictor of consequence? J Couns Psychol 62 4 568

-

PJ Chao JJ Steffen EM Heiby 2012 The effects of working brotherhood and customer-clinician ethnic match on recovery status Community Ment Health J 48 91 97

-

BJ Taber TW Leibert VR Agaskar 2011 Relationships among client–therapist personality congruence, working alliance, and therapeutic outcome Psychotherapy 48 iv 376

-

BSK Kim GF Ng AJ Ahn 2005 Effects of customer expectation for counseling success, customer-counselor worldview match, and client adherence to Asian and European American cultural values on counseling process with Asian Americans J Couns Psychol 52 ane 67 76

-

C Flückiger AC Re Del BE Wampold AO Horvath 2019 Alliance in developed psychotherapy Psychother Relationsh Work 1 24 77

-

C Graßmann F Schölmerich CC Schermuly 2020 The relationship betwixt working alliance and client outcomes in coaching: a meta-assay Human being Relat 73 ane 35 58

-

JC Norcross 2010 The therapeutic relationship BL Duncan SD Miller BE Wampold MA Hubble Eds The eye and soul of alter: delivering what works in therapy American Psychological Clan 113 141

-

J Bowlby 1978 A secure base. Clinical applications of zipper theory Routledge London

-

MJ Constantino DB Arnkoff CR Glass RM Ametrano JZ Smith 2011 Expectations J Clin Psychol 67 2 184 192

-

F Falkenström Yard Kuria C Othieno Thousand Kumar 2019 Working alliance predicts symptomatic comeback in public infirmary—delivered psychotherapy in Nairobi, Republic of kenya J Consult Clin Psychol 87 one 46

-

Duncan B, Miller S, Sparks J, Manzo L. Award Thy Client. Psychcritiques. 2004;49.

-

AJ Blow DH Sprenkle SD Davis 2007 Is who delivers the handling more important than the treatment itself? The office of the therapist in mutual factors J Marital Fam Ther 33 3 298 317

-

AJ Blow TM Timm R Cox 2008 The role of the therapist in therapeutic change: does therapist gender matter? J Fem Fam Ther 20 1 66 86

-

LA Johnson BE Caldwell 2011 Race, gender, and therapist confidence: furnishings on satisfaction with the therapeutic relationship in MFT Am J Fam Ther 39 4 307 324

-

P Staczan R Schmuecker M Koehler J Berglar A Crameri A Wyl von M Koemeda-Lutz P Schulthess V Tschuschke 2017 Effects of sexual activity and gender in x types of psychotherapy Psychother Res 27 1 74 88

-

M McGoldrick J Giordano Northward Garcia-Preto 2005 Ethnicity and family therapy Guilford Press

-

G Echterhoff ET Higgins JM Levine 2009 Shared reality: Experiencing commonality with others' inner states about the globe Perspect Psychol Sci four 5 496 521

-

AH Eagly 1983 Gender and social influence: a social psychological analysis Am Psychol 38 nine 971

-

SL Bem 1981 Gender schema theory: a cognitive account of sex typing Psychol Rev 88 four 354

-

AH Eagly 1987 Reporting sex differences Am Psychol 42 vii 756 757

-

AH Eagly Westward Wood 2016 Social function theory of sexual practice differences The Wiley Blackwell

-

Wiggins JS. Agency and communion as conceptual coordinates for the understanding and measurement of interpersonal beliefs. 1991.

-

AH Eagly Westward Wood 1991 Explaining sex differences in social beliefs: a meta-analytic perspective Pers Soc Psychol Bull 17 3 306 315

-

AL Baier Ac Kline NC Feeny 2020 Therapeutic alliance as a mediator of change: A systematic review and evaluation of research Clin Psychol Rev 82 101921

-

MJ Constantino AE Coyne EK Luukko K Newkirk SL Bernecker P Ravitz C McBride 2017 Therapeutic brotherhood, subsequent change, and moderators of the alliance–outcome clan in interpersonal psychotherapy for depression Psychotherapy 54 2 125

-

Birnstein M. Wem kann ich vertrauen? Alter von PsychotherapeutInnen als Entscheidungskriterium von PatientInnen bei Ihrer TherapeutInnenwahl. Master Thesis an der Donau Universität Krems. 2015. http://webthesis.donau-uni.air-conditioning.at/thesen/90123.pdf Abruf 20.4.2021.

-

SC Black Due east Gringart 2019 The relationship betwixt clients' preferences of therapists' sex and mental health support seeking: an exploratory written report Aust Psychol 54 4 322 335

-

K Kuusisto T Artkoski 2013 The female therapist and the customer's gender Clin Nurs Stud ane three 39 56

-

We Fowler WG Wagner 1993 Preference for and comfort with male person versus female counselors amidst sexually abused girls in individual treatment J Couns Psychol 40 1 65

-

JK Swift JL Callahan One thousand Cooper SR Parkin 2018 The touch of all-around client preference in psychotherapy: a meta-assay J Clin Psychol 74 11 1924 1937

-

DC Fujino Southward Okazaki M Young 1994 Asian-American women in the mental health system: an examination of ethnic and gender match betwixt therapist and client J Customs Psychol 22 2 164 176

-

EE Jones JL Krupnick PK Kerig 1987 Some gender effects in a brief psychotherapy Psychother Theory Res Pract Train 24 3 336

-

JG Cottone P Drucker RA Javier 2002 Gender differences in psychotherapy dyads: Changes in psychological symptoms and responsiveness to handling during 3 months of therapy Psychother Theory Res Pract Railroad train 39 four 297

-

JM Jerrell 1995 The effects of customer-therapist match on service apply and costs Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res 23 ii 119 126

-

LA Bryan C Dersch South Shumway R Arredondo 2004 Therapy outcomes: customer perception and similarity with therapist view Am J Fam Ther 32 i 11 26

-

Cooper M, Van Rijn B, Chryssafidou E, Stiles WB). Activity preferences in psychotherapy: what do patients want and how does this relate to outcomes and alliance? Couns Psychol Q. 2021;1–24.

-

JD Huppert LF Bufka DH Barlow JM Gorman MK Shear SW Woods 2001 Therapists, therapist variables, and cognitive-behavioral therapy outcome in a multicenter trial for panic disorder J Consult Clin Psychol 69 5 747

-

D Bowman F Scogin G Floyd N McKendree-Smith 2001 Psychotherapy length of stay and outcome: a meta-assay of the consequence of therapist sexual activity Psychother Theory Res Pract Train 38 2 142

-

K Kamenov C Twomey M Cabello AM Prina JL Ayuso-Mateos 2017 The efficacy of psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy and their combination on functioning and quality of life in depression: a meta-assay Psychol Med 47 three 414 425

-

Häder S. Auswahlverfahren bei Telefonumfragen. 1994.

-

Kirschner H-P. ALLBUS 1980: Stichprobenplan und Gewichtung. In: Mayer KU, Schmidt P (Hrsg) Allgemeine Bevölkerungsumfrage der Sozialwissenschaften. Beiträge zu methodischen Problemen des ALLBUS 1980. Campus, Frankfurt a.Chiliad. 1984.

-

C Albani G Blaser M Geyer G Schmutzer E Brähler 2011 Ambulante Psychotherapie in Deutschland aus Sicht der Patienten Psychotherapeut 56 1 51 60

-

Seligman ME. The effectiveness of psychotherapy: the consumer reports study. 1995.

-

South Hartmann 2006 Die Behandlung psychischer Störungen: Wirksamkeit und Zufriedenheit aus Sicht der Patienten; eine Replikation der" Consumer Reports Study" für Deutschland Psychosozial-Verlag

-

Statista. Häufigste Erkrankungen in Deutschland, retreieved, 2021.xi.thirteen. 2011. https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/234025/umfrage/haeufigste-psychisch-erkrankungen-in-deutschland-nach-geschlecht/.

-

German gild for psychiatry and psychotherapy. Valide Antworten auf zahlreiche Fragen, retreived, 2021.11.xiii. 2021. https://www.dgppn.de/schwerpunkte/zahlenundfakten.html.

-

R Core Team 2020 A language and surround for statistical computing R Foundation for Statistical Calculating

-

E Schmider M Ziegler Due east Danay 50 Beyer One thousand Bühner 2010 Is information technology really robust? Methodology 6 147 151

-

JH Flaskerud 1990 Matching client and therapist ethnicity, language, and gender: a review of inquiry Issues Ment Health Nurs 11 four 321 336

-

C Zlotnick I Elkin MT Shea 1998 Does the gender of a patient or the gender of a therapist affect the treatment of patients with major depression? J Consult Clin Psychol 66 4 655

-

EH Fisher 1989 Gender bias in therapy? An analysis of patient and therapist causal explanations Psychother Theory Res Pract Train 26 three 389

-

RL Hatcher JA Gillaspy 2006 Development and validation of a revised short version of the Working Alliance Inventory Psychother Res xvi one 12 25

-

ML Nelson 1993 A current perspective on gender differences: Implications for inquiry in counseling J Couns Psychol 40 200 209

-

Fifty Kottje-Birnbacher 1994 Übertragungs-und Gegenübertragungsbereitschaften von Männern und Frauen Psychotherapeut (Berlin) 39 1 33 39

-

R Ulberg P Johansson A Marble P Høglend 2009 Patient sexual practice every bit moderator of effects of transference interpretation in a randomized controlled study of dynamic psychotherapy Can J Psychiatry 54 2 78 86

-

Thousand Tolle A Stratkötter 1996 Die Geschlechtszugehörigkeit von Therapeutinnen und Therapeuten in der psychotherapeutischen Arbeit: ein integratives Modell F Breuer Eds Qualitative Psychologie Springer 251 266

-

B Schigl 2018 Gender und Psychotherapieforschung B Schigl Eds Psychotherapie und Gender. Konzepte. Forschung. Praxis Springer 117 168

-

JS Ogrodniczuk Nosotros Piper AS Joyce 2006 Differences in men's and women'due south responses to brusque-term group psychotherapy Psychother Res 14 231 243

-

S Burton E Blair 1991 Task conditions, response formulation processes, and response accuracy for behavioral frequency questions in surveys Public Opin Q 55 ane 50 79

-

PM Niedenthal S Kitayama Eds 2013 The middle'south eye: Emotional influences in perception and attending Academic Press

-

HÖ Ayhan Due south Işiksal 2005 Retentiveness think errors in retrospective surveys: a contrary record check report Qual Quant 38 5 475 493

-

Federal sleeping accommodation of psychotherapist. 2016. Retrieved on 2021.x.15 https://www.bptk.de/.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt Deal. Open Admission Funding past the Publication Fund of the TU Dresden.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

KP: Conceptualization. IS: Methodology, writing of the main paper. KP and EB: Software and Validation, CA: Investigation and data management. All authors read and canonical the last manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data of the study at hand were deputed by the University of Leipzig and approved by their ethic committee (Blessing number: WREBAM16102006DGPS). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this written report. The methods of information collection were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (equally revised in 1983). This manuscript does non report on or involve the utilize of whatsoever creature or human information or tissue.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional data

Publisher'due south Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatever medium or format, as long equally you lot give appropriate credit to the original author(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and betoken if changes were fabricated. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Eatables licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Artistic Eatables licence and your intended use is non permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission direct from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

Almost this article

Cite this article

Schmalbach, I., Albani, C., Petrowski, One thousand. et al. Customer-therapist dyads and therapy outcome: Does sex matching matters? A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol 10, 52 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00761-four

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00761-4

Source: https://bmcpsychology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40359-022-00761-4

0 Response to "Matching Client and Therapist Ethnicity Language and Gender a Review of Research"

Post a Comment